Umgebungen

A Sustainable Journey into the Umwelt of Peatland Life

As an artist inspired by ecology, this project evolved out of a sense of responsibility to respond to the effects of our encroachment on the natural world and its ever-dwindling species numbers. After watching a BBC2 documentary called ‘Secrets in the Peat’ which highlighted that bog slides were an issue affecting peatlands, I found that this connected to previous work which focused on man-made scars on the landscape, I was intrigued.

My response was to begin research into creating an immersive art project that promotes the value of our living, breathing peatlands (Marshall et al., 2021), whilst exploring the concepts of umgebungen (environments) and umwelt (environment as perceived by another being) by exploring artistic and scientific practice-based research methodologies (Candy and Edmonds, 2018). The project aims to observe and promote the value of reciprocal and intimate relationships between plant beings, human and nonhuman animals.

Peatlands' long-term ability to store carbon (UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, n.d.) often seems overlooked in favour of preserving and planting trees. Yet they can store twice the amount found in all the world’s forests (IUCN UK Peatland Programme, 2024), so why is their importance in our battle against the climate crisis still underrepresented in the public domain, whilst that of trees and forests remains high in public awareness? (Hughes, 2021).

It goes without saying that trees and forests should be held in high regard, saved and preserved, but past efforts to capture carbon have resulted in trees being placed on peatlands, when simply preserving the peatland in the first place would have captured and stored more carbon long term. (Rogers, 2022; Mander, 2024)

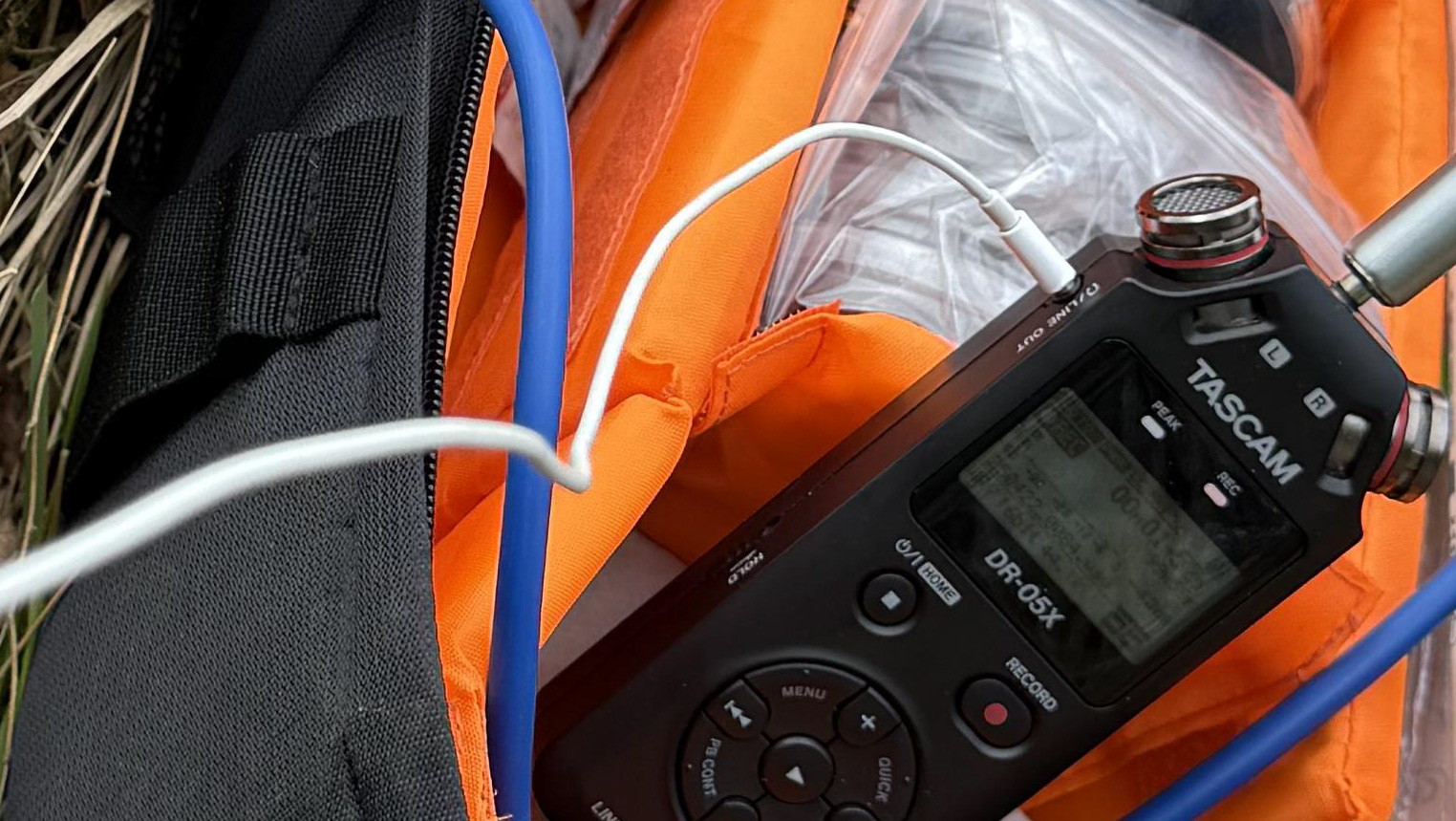

The project aimed to explore peatland habitats above ground, at the surface and below the surface. I have undertaken early exploratory enquiries using photographic, cinematographic, audiological, material, mycelial, as well as data-derived research to build a picture of peatlands.

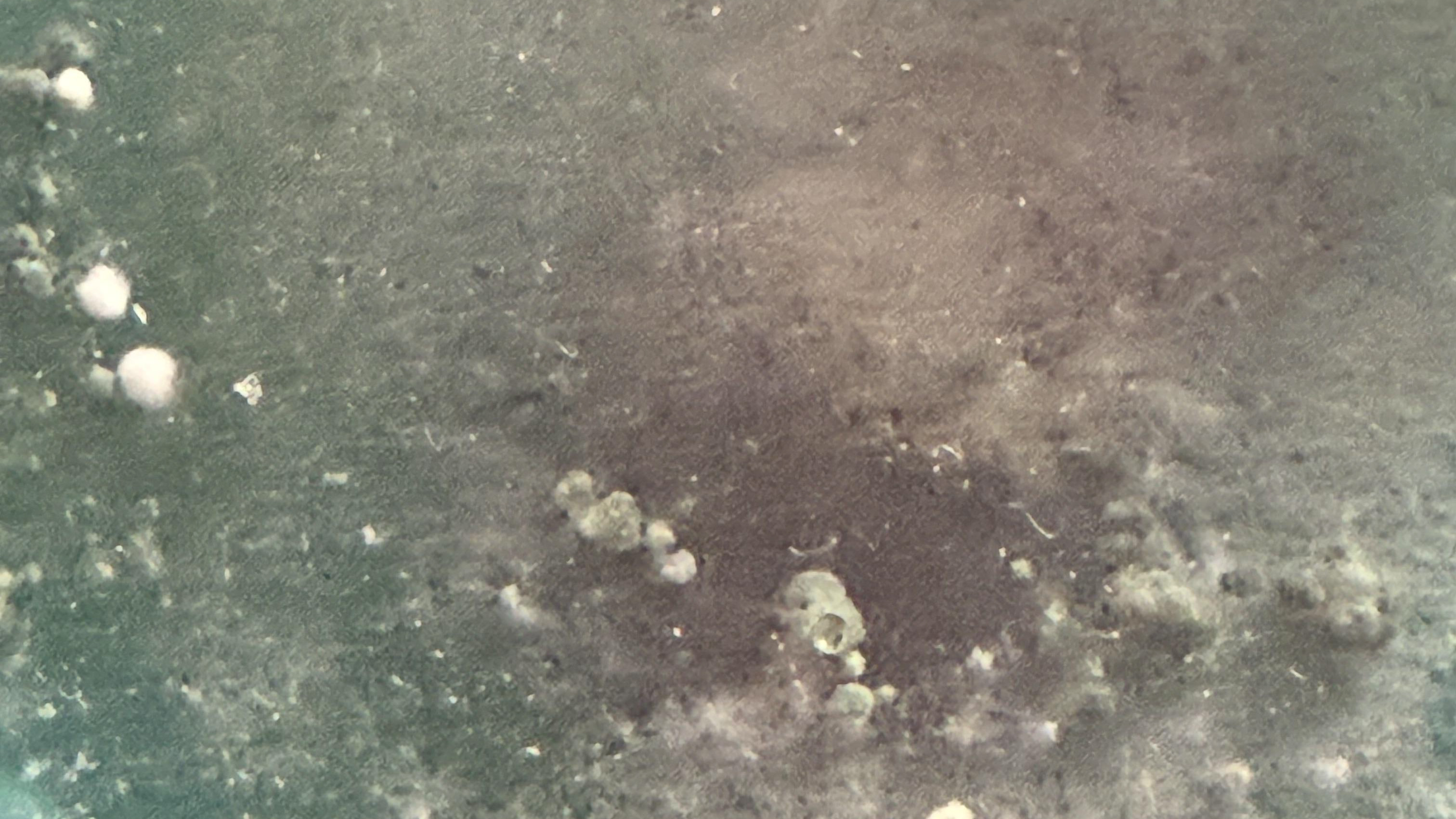

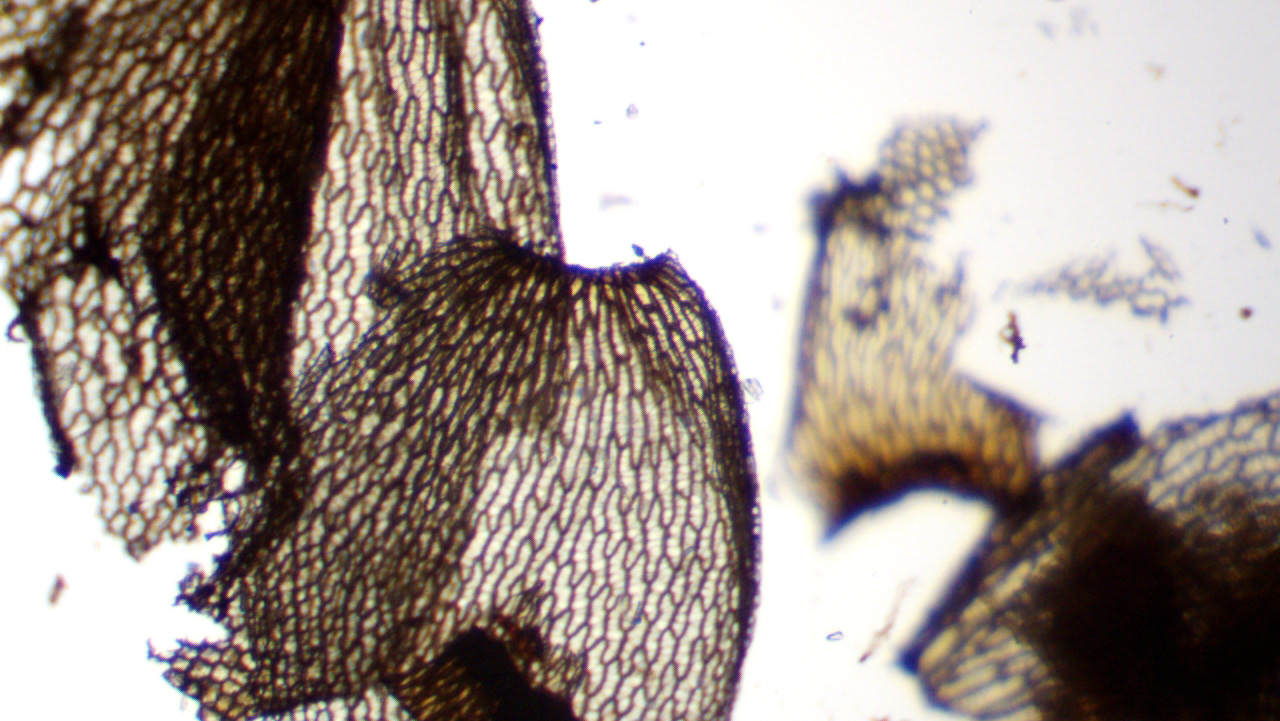

Speculative experiments of below-ground ecology using audio and mycelium looked to uncover some of the subsurface stories of peatlands, and some early experiments with CGI tools such as Blender and VR will eventually be incorporated to add another layer to immersive video and cinematography. This has stemmed from greater scientific awareness and a growing understanding of the complexity of the natural world, particularly in relation to peatland ecology. This was formed while collecting samples on fieldtrips during spring 2025, where sterile charcoal swab kits were used to take soil samples and placed on malt extract agar plates at each site. To my amazement, every time I tried to grow mycelium, it worked, and this spurred me on to develop this further into time-lapse sequences.

Research into sustainable materials has stemmed from my understanding of the materials associated with peatland restoration and plant products associated with paludiculture on peatlands. This research is of ground level, but also connects to below-ground research because some of the materials are used to stabilise soil.

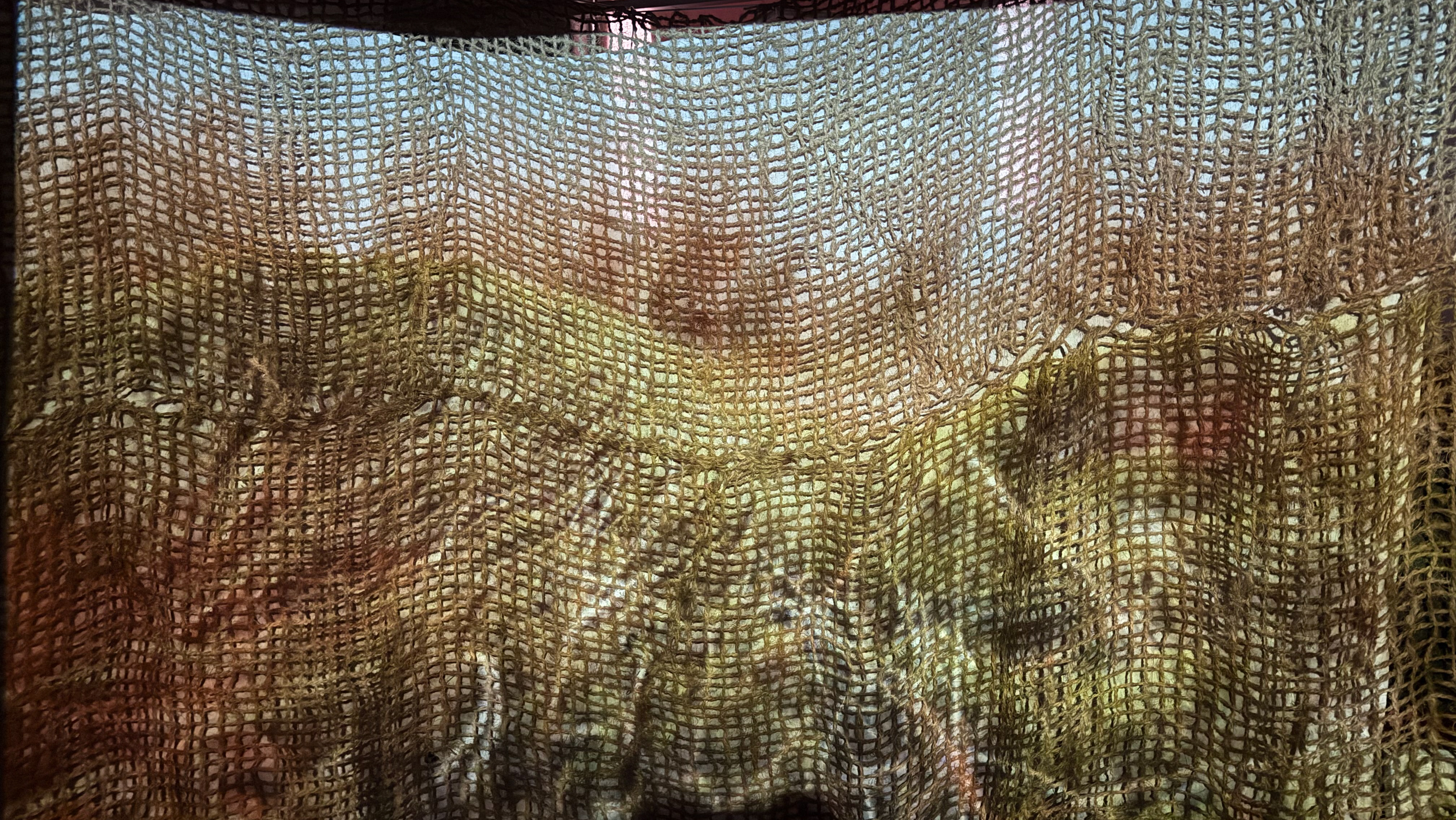

The bog blanket I have made from wool and hessian aims to reflect blanket bogs. It is made from natural fibres used to restore bogs; it is a mise en abyme (Daston, 2008) of peatland restoration, reflective of both above and below ground research. It is made from materials associated with peatland restoration, these are the fibres that hold the mistreated soils together during restoration, the bog blanket serves as a visual interpretation of the plant life above the ground, it may well end up being buried again below the ground before being dug up to capture the scents and colours from peaty soils to evoke the senses whilst in a gallery.

A bog box is in planning but is not yet built. This is due to a delay in obtaining the plants. In the meantime, I will ensure it is ready for when I get the plants. I hope to include audio equipment with the bog box so that it can be used to communicate that peatlands are living, breathing places.

Above-ground research has been undertaken into hydrology data using Sentinel satellite images, along with a speculative sequence created from images of sphagnum moss made from photographs taken whilst on field trips.

Cinematography that looks at the plants and tries to imagine the world as viewed from the umwelt of another being is being developed from site visits in different locations, upland blanket bogs and lowland raised bogs, as well as afforested peatland, all strikingly different environments. Each time I carry out field trips I collect as much photographic evidence and videography as possible as well as audio, these are combined and manipulated later using Adobe Premier Pro, AI generated voice is also overlayed, the narration adds insight into what the conditions are at each place, this is especially evident in ‘Plantation’ where the film is set within an afforested area of peatlands. The voice reminds us that this place, although beautiful, is not right.

These quite different experimental lines of inquiry all serve to gather multi-layered information where ‘knowledge is being derived from doing’ (Barrett and Bolt, 2012).

When these layers are combined at a later date, each line of inquiry will serve to connect the senses and evoke a feeling of a place away from the geographical place and reflect the complexities of these environments.

The hope is that people can see peatlands are not simply places with little value, and that they are, in fact, important, unique, valuable places that need our protection. Many of them might be damaged, but they are important and worth fighting for. Our dominance over the world’s resources has left little for nonhumans and nature (More Than Human Life, n.d.), so we need to work to make creative solutions to the problems we face. At times, the alternative is believing that the game is over, it’s too late, there’s no sense trying to make anything any better. (Haraway, 2016)

This project is a collaborative effort, reaching out to nature partners, widening my horizons (Giri, 2002). The transdisciplinary approach and ‘making-with’ (Haraway, 2016) has instilled a greater understanding of peatland ecology and the work being undertaken by scientists keen to embrace Arts-Based Interventions (ABIs) to support sustainability-oriented transdisciplinary research. Horvath et al. (2025).

Reaching out to experts in the field has enabled me to access places and research that would not otherwise have been available to me. Without their support, access would have been impossible in the worst case and much harder at best. Similarly, the exposure of new areas to research through carrying out art-science activities as a result of my MA has opened avenues of exploration.

Focussing on the work of others carrying out ecological arts practice-based research (Candy and Edmonds, 2018), such as Tracey Hill, Miranda Whall, Marshmallow Laser Feast, or Kerry Morrison, are just a few of the many artists who have inspired me and fed into my research of peatland ecology.

There is even collaboration between me and the landscape as it offers me more insight and inspiration as time goes on. This is also true of the mycelium, which did not put itself into the petri dish and create a time-lapse of itself. It might not even be able to grow in peatland conditions; it could just be a spore that landed there on a breeze. Similarly, I cannot create mycelium, but I might have helped a mycelial spore grow that might not have otherwise been able to; either way, the time-lapse footage I have made is a collaborative effort between myself and the fungi.

There is a lot of work still to do if I am to help bridge the gap and supply fresh insights (Berry-Frith, 2003) and knowledge to our underrated peatlands and contribute to cultural and ecological understanding.

I am behind in some respects. I would have preferred the small bog blanket to be complete by now, so I will make this a priority, along with making a bog box. I also plan on upskilling and practising technical skills such as CGI, LiDAR, VR and learning more about projecting and the technical set-up of an immersive exhibition.

Issues with light in my time-lapse footage need to be resolved, and cinematography would benefit from a better understanding of peatland creatures’ vision and/or their senses, do they see in colour, full spectrum, black and white or 360° vision perhaps?

More research into fungal communities of peatlands is needed, as I am aware that they should host ericoid mycorrhizal fungi (EMF), but without further learning and better equipment, I have no way of identifying them.

Ethical making and sourcing materials for the blanket work are important to the project. I am sure at times this will be a challenge, but it’s a worthy cause. Our dominance over the world’s resources has left little for nonhumans and nature (More Than Human Life, n.d.) Finding artists who also look to build a sustainable practice can be really encouraging, as are the many other people working across many disciplines to save and restore nature. People have the solutions to many of the problems we face; we just need to work together and think outside the box.

In the future, I would like to work more closely with scientists on this project, so I will continue to break down barriers (Giri, 2002) and make ‘kin’, but in the meantime, I will build on this project and my capacity to narrate the story of our connection to living, breathing peatlands.